At the start of the New Year, I began growing mung bean sprouts on the kitchen counter. Nothing ambitious: a glass jar, a handful of dry beans, water, patience. It was partly practical — a small attempt to eat better — and partly seasonal, a gesture of beginning again.

But as so often happens, attention did the rest.

Each morning and evening I rinsed the beans, drained the water, and tilted the jar back into place. Within a day, change began. Roots appeared. Pale shoots followed. By the third day, the jar was quietly alive with direction and momentum. Nothing dramatic. Nothing expressive. Just steady response.

Watching this simple process unfold gave rise to a set of thoughts that have stayed with me.

There is something quietly reassuring in discovering that:

-

- order doesn’t require intention

- meaning can emerge from conditions

- responsiveness is not the same as consciousness

A seed doesn’t care —

but it is exquisitely attuned.

That distinction matters far beyond botany.

A mung bean has no brain, no awareness, no sense of purpose. It does not want to grow. It does not know that it is growing. And yet, when the conditions are right — moisture, warmth, oxygen — it responds. Enzymes activate, stored energy is released, cells divide, and a process begins that looks uncannily like purpose.

But it isn’t.

What the seed demonstrates is something both humbling and quietly radical: meaning can arise from structure rather than intention. Order can appear without a planner. Direction can emerge without desire. Life can move forward without knowing why.

“Life is not obliged to make sense to us.”

— Richard Dawkins

We tend to assume the opposite about ourselves.

Much of modern human anxiety is rooted in the belief that meaning must be consciously created: unless we are constantly choosing, narrating, justifying, our lives risk becoming meaningless. We speak as if significance must always be meant by someone, preferably articulated, preferably defensible.

And yet, much of what shapes us most deeply happens long before we have words for it.

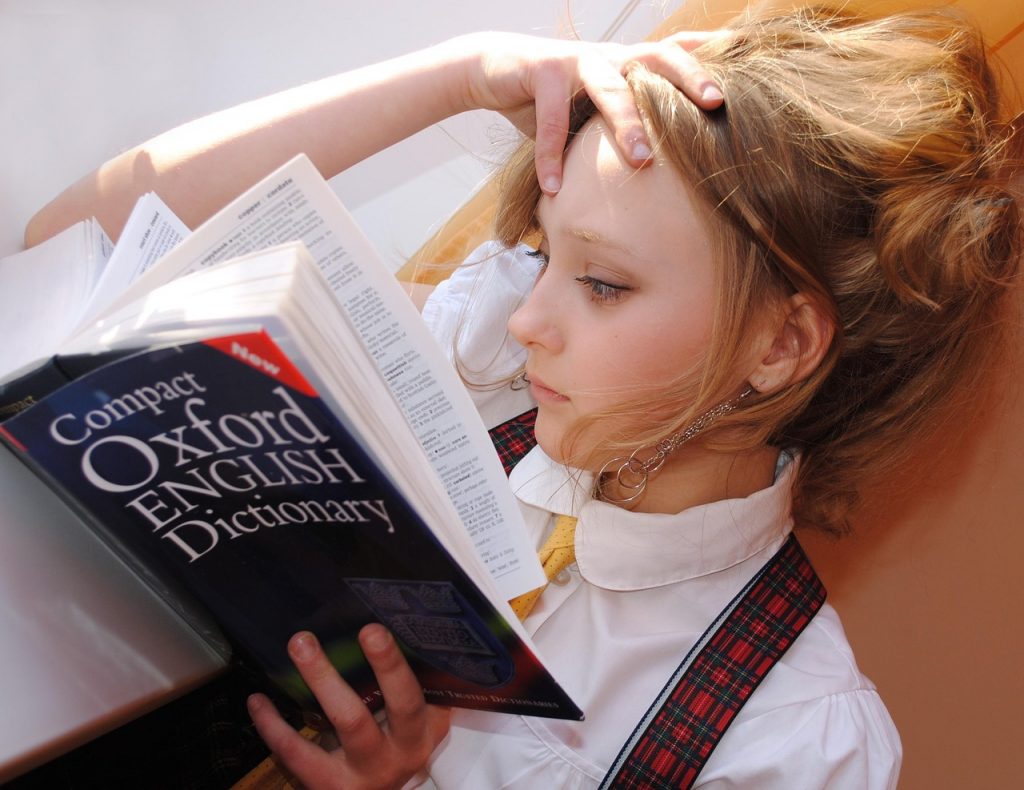

Which brings us to language.

There is a quiet assumption, widely shared and rarely examined, that meaning only exists where language exists. I certainly absorbed this idea early on: that without words, symbols, and narratives there could be no meaning, only blind mechanism. Animals, plants, seeds may be somehow alive, but they are not conscious of their existence because they do not have language. But is this assumption true under closer attention? Language does not so much create meaning as name it. Long before we describe a situation as safe or threatening, nourishing or hostile, our bodies are already responding. Long before a child can articulate belonging or neglect, those conditions are shaping who they become. Meaning, in this sense, precedes language. Language arrives later, not as the origin of significance, but as its echo.

Taken seriously, this idea does not just reshape education or psychology; it also presses uncomfortably on our concepts of religion.

If meaning precedes language, then religion becomes structurally vulnerable in a way it rarely acknowledges. Religious systems depend on language to define, order, and sanctify a reality that was already unfolding long before it was named. Just as the seed germinates without reference to our metaphors, doctrines, or reverence, the world generates complexity, order, and awe without requiring theological narration. Religion, in this light, does not create meaning but gathers around it — stabilising, preserving, and sometimes claiming ownership of what would otherwise continue unbothered. The danger is not that religion is false, but that it mistakes itself for the source rather than the afterimage of meaning: a linguistic architecture built around processes that do not need to be spoken in order to be real.

“There are no facts, only interpretations.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche

Seen this way, the seed is not a lower form of life waiting for consciousness to redeem it. It is a reminder that attunement comes before articulation.

This has implications for how we think about human agency. To say that meaning can emerge from conditions is not to deny responsibility or choice. It is to relocate them. Agency is not constant control; it is responsiveness within constraints. The skill is not to will meaning into existence, but to recognise what kinds of environments allow growth — in ourselves and in others.

And this is where education enters the picture.

Much of contemporary schooling still reflects a modernist inheritance: knowledge divided into discrete subjects, timetabled and assessed in isolation. Biology here. Chemistry there. Physics somewhere else. Meaning nowhere in particular.

We teach biology largely as a catalogue of facts — cell structures, taxonomies, cycles, pathways — accurate, necessary, and often lifeless. Rarely do we teach it as the study of responsive systems. We talk about genes, but not environments. About mechanisms, but not emergence. Students learn that a seed needs water, warmth, and oxygen, yet miss the astonishing implication: life does not need a mind in order to organise itself.

By separating biology from physics and chemistry, we also reinforce a subtle illusion — that life is something apart from the rest of reality, rather than a continuation of it. As if metabolism were not chemistry in motion. As if growth were not physics slowed down and shaped by constraint. As if living systems did not obey the same laws as rivers and stars, only at a different scale.

A more truthful curriculum would dissolve these boundaries.

“What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.”

— Werner Heisenberg

Imagine teaching “life” as a conversation between disciplines:

chemistry becoming organised,

physics learning to linger,

energy flowing through matter long enough to notice itself.

In such a curriculum, a sprouting seed would not be a marginal example but a foundational one. Students would be invited to ask not only what happens, but what it reveals: that responsiveness predates consciousness, that attunement is older than intention, that meaning does not need to be imposed in order to arise.

The ethical consequences would follow naturally. Instead of moralising failure, students might ask better questions: What conditions were missing? What environments are we creating? What do we reward, nourish, neglect?

Education, at its best, does not manufacture outcomes.

It creates conditions.

A seed doesn’t care.

But it responds.

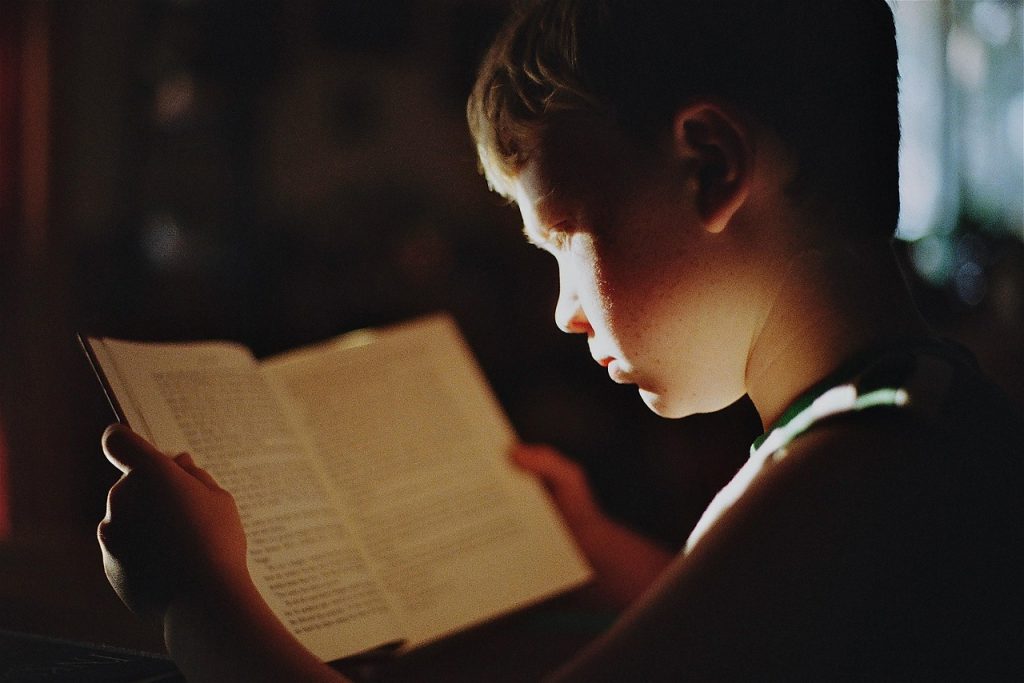

So do children.

So do communities.

And, more often than we like to admit, so do we.

Perhaps part of the task of education — and of adult life — is to relearn this modest, hopeful truth: that meaning does not always need to be pursued or declared. Sometimes it only needs the right conditions in which to emerge.

“The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.”

— Albert Einstein