I did not expect a pilgrimage. All I wanted, on a cold Berlin morning, was a simple desk in my local library. A familiar refuge where I could coax myself into writing. Instead, I arrived to find the doors barred and the building shrouded in scaffolding. Closed for refurbishment. And yet even that felt oddly hopeful: a library being tended to, repaired, protected. A chrysalis in plywood. Still, it left me homeless for the day, so I pointed myself into the centre of Berlin and followed a vague instinct in search of a different reading room.

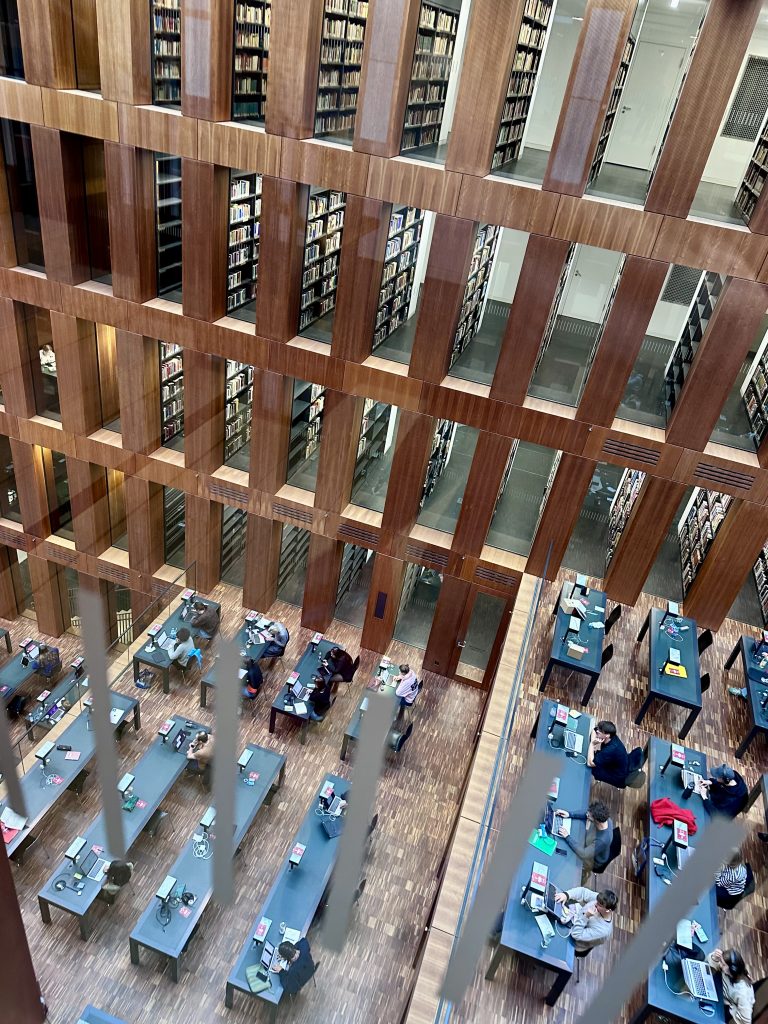

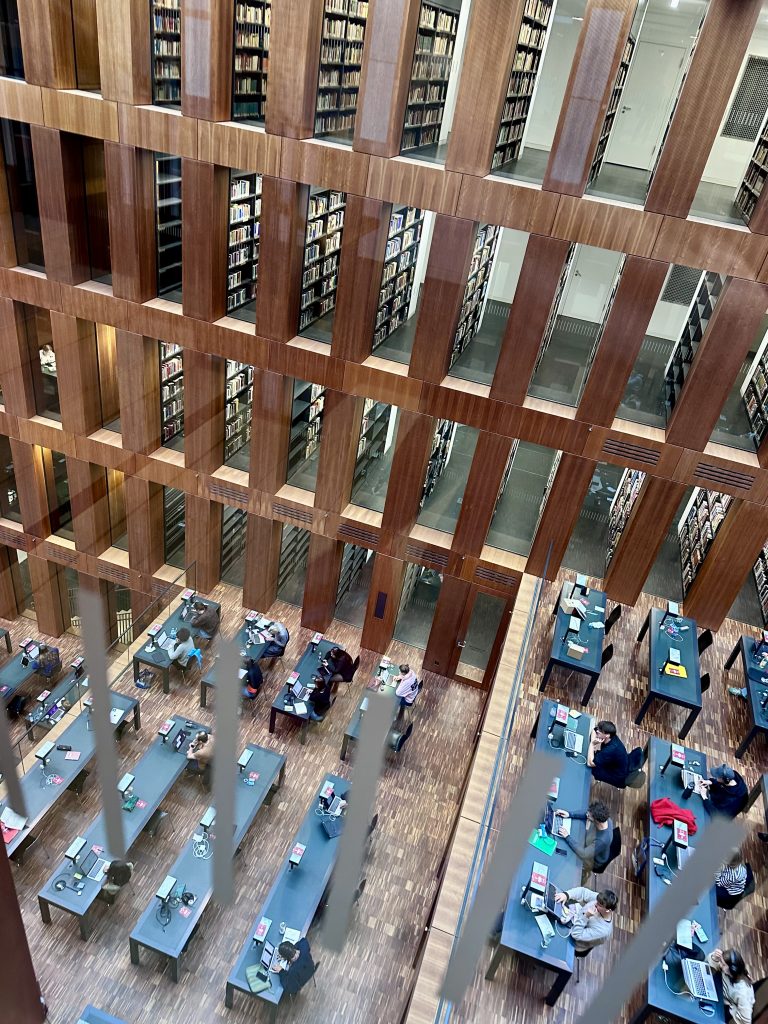

By early afternoon I was standing inside the Humboldt University Library, in the central Jacob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum — a building completed in 2009 at a cost of roughly €150 million, a temple to light and linearity, a modern cathedral carved out of honey-coloured wood. I had never been inside before. I found my way up several flights of stairs, past quiet students and moving columns of books, until I arrived in the library’s great central atrium.

There are moments when atmosphere becomes an event, as if the air thickens with meaning, as though the space itself has a pulse. That is what happened. The first glance into the atrium felt like encountering a new idea before you have the words for it.

The room opened before me in tiers, receding downwards in vast wooden frames, each level lined with narrow study desks illuminated by soft rectangular lamps. Above, the ceiling dissolved into a grid of skylights, a geometry of glass and daylight. Below, hundreds of young people bent over books and laptops, headphones cocooning them, highlighters poised like tiny torches hunting for truth in margins. It was an amphitheatre of thought, tier upon tier of silent striving, human concentration arranged like an inverted ziggurat.

The sight moved me more than I had anticipated. I had often studied in the ancient libraries of Oxford, with their stone floors worn by centuries of scholars and portraits of stern-faced alumni glaring down with a mixture of judgement and encouragement. But this — this modern Berlin chamber with its clean lines and its open light — held its own kind of splendour. If Oxford’s libraries feel like the weight of the past pressing lovingly upon you, the Grimm-Zentrum feels like the future stretching out somewhere beyond the roof.

And suddenly I felt small and young again, in the most wonderful way.

A Place Where the World Learns How to Think

What struck me first was the sound — or rather, the absence of it. The quiet in a library is not mere silence. It is a collective agreement, a social pact, a voluntary reverence. The students around me were not quiet because they were told to be. They were quiet because they were invested. Because something mattered.

Then came the smell — that unmistakable perfume of libraries everywhere:

waxed linoleum; varnished wood; warm dust that rises from the turning of pages; and above all that distinctive scent of old books, a mixture of paper, glue, ink, and time itself. It carries, always, a faint edge of mystery – a reminder that knowledge ages like a living thing.

As I sat down on the highest tier, overlooking this incredible geometry of minds at work, it occurred to me that libraries are among the few places left in modern life where human concentration is visible. We watch it manifest physically: in posture, in scribbles, in slow-page turns, in the absorbed stillness of someone who is trying to understand.

The atmosphere was electric but hushed, charged but respectful. There were students mapping out theses with coloured pens, others scrolling through academic articles, some chewing their pens absentmindedly while staring into middle distance — that universal gesture of a mind wrestling with a concept. There were those who looked exhausted but determined, and others who looked exhilarated by a sentence they had just discovered. Every face was a small story of effort.

This collective striving was profoundly moving. It made visible something we often forget: knowledge is crafted, not downloaded. Even with all the technology around them, these students were still doing the slow, patient work that makes civilisation possible. Research is not glamorous. It is hours of searching, scanning, discarding, re-reading. Yet they persisted.

Watching them, I felt privileged — almost intrusive — as though I were witnessing a kind of secular liturgy.

This Is Not an Anti-AI Eulogy. Quite the Opposite.

Let me say this clearly, and early, because sentiments like mine are often misinterpreted: this is not a rear-guard lament against AI.

No pious calls to return to pre-digital methods. No false nostalgia. No technophobia.

I embrace AI wholeheartedly. I use it every day, and I consider it one of the most extraordinary tools ever created. It accelerates learning, supports human creativity, and holds vast potential for everything from agriculture to medicine to interplanetary exploration. It will help build the colonies on Mars long before we finish debating whether rocket fuel is environmentally friendly.

So this reflection is not a plea for a world without technology. It is instead an attempt to articulate something different: that libraries and AI are not adversaries.

They are partners.

One is where the human mind trains its depth; the other is where it extends its reach.

Libraries teach us how to think.

AI helps us learn faster once we know how.

The library is the gymnasium of cognition.

AI is the exoskeleton.

We need both.

A Secular Temple — or Something More

As I sat in the top tier of that atrium, I realised that all my senses were activated at once: sight, sound, smell, touch, and the quiet murmur of pages turning like a heartbeat for the whole building. It was almost too much. It bordered on the religious.

If you believe in God, you could easily imagine gratitude rising like incense: look what humanity — the species fashioned out of dust and breath — has managed to build. Look how our curiosity has unfolded into architecture, scholarship, craft, and a hunger for understanding that seems inexhaustible.

If you do not believe in God, the miracle remains.

After all, what could be more astonishing than this? That the random electrical impulses arising from an indifferent universe have generated organisms who sit together in vast wooden halls reading about Mesopotamia, quantum mechanics, marine ecosystems, political philosophy, medieval manuscripts, and machine learning algorithms. That atoms born in supernovae now write essays on ethics and the shape of a meaningful life.

Even the most hardened atheist cannot deny the improbability, the majesty of that.

To sit in a library is to witness a miracle in motion — a civilisation rehearsing its own continuation.

The Invisible People Who Make It Possible

It is easy, in moments of beauty, to forget the infrastructure that supports them. But libraries are not spontaneous miracles. They are daily, deliberate acts of civic generosity.

Someone designed this building with its lightwells, its tiers, its acoustics, its quiet. Someone else built it, brick by brick, panel by panel. Others maintain it, polish the floors, fix the lamps, organise the recycling, restock the bathrooms, oil the doors so they close softly.

Then there are the librarians, the custodians of order in our age of chaos. The ones who curate, classify, preserve, and patiently help bewildered visitors locate that one book whose title they have partially forgotten. They are the guardians of continuity, the keepers of fragments, the quiet historians of our intellectual life.

Yesterday, I watched a librarian register new readers at the desk. One of them was me. The young man helping me was in his early twenties, wearing a university hoodie, and fascinated by my British passport. He asked why the text was printed both in English and French. He was curious about British attitudes to Europe, about why I had come to Berlin, about what I was planning to write.

There was no transactional coldness in him. Only a genuine hunger to learn, to connect, to understand. It was a small moment, and yet it added a human warmth to the architecture around us. It reminded me that libraries are not only spatial achievements; they are social ones. They bring together people who believe — perhaps stubbornly, courageously — that knowledge should remain accessible to all.

And yes, I felt grateful. Deeply grateful. In an age dominated by cynicism about governments, it is worth remembering that states still choose to spend millions on libraries, archaeology departments, social sciences faculties, digitisation projects, and the preservation of knowledge. This is not trivial. It is evidence of a civilisation still investing in its own mind.

A Place Where My Own Creativity Woke Up

I did not plan to begin outlining a new novel yesterday. But the effect of sitting in that atrium was galvanising. The sight of hundreds of young minds in motion, the geometry of the architecture, the warm glow of the wood, the filtered daylight, the portraitless vastness that made every student their own protagonist — it all stirred something in me.

Creativity, I am convinced, is contagious. We borrow the electricity of others. When you place yourself in an environment charged with intellectual purpose, something inside you aligns. Ideas begin to organise themselves. Sentences appear without being summoned. Pages begin to form.

That is exactly what happened.

Within an hour of sitting down, my mind was in overdrive, casting threads between ideas I had been carrying for months, imagining scenes, characters, dilemmas. The space did not merely host my creativity; it provoked it. I left with the outline of my next book beating quietly inside my bag.

Why This Matters for the World Our Children Inherit

As I gazed into the atrium, I kept thinking about the thousands of young people around the world who will never experience something like this — who study in overcrowded classrooms, or at kitchen tables, or not at all. And then I thought of the students who do have this privilege and perhaps take it for granted, because we all take blessings for granted when they become part of the wallpaper of our days.

A library like this is not a neutral space.

It is a statement.

A declaration of values.

A place where a society says to its young:

Take this. Explore. Learn. Write. Think. Question. Become. We believe you are worth the investment.

My hope is that such spaces will not become relics. That they will not be drowned by the easy seductions of instant information, nor by political short-sightedness, nor by economic austerity. May libraries continue to stand as cathedrals of collective education, where young people can enter free of charge and leave richer in spirit, sharper in thought, and braver in imagination.

A Final Word of Gratitude

So this is my homage — not to nostalgia, but to possibility. To the people who keep these spaces alive. To the students who fill them. To the architects who imagine them. To the librarians who protect them. And yes, to the governments and taxpayers whose resources make them real.

Most of all, it is an expression of gratitude for the simple miracle that humans still gather in large wooden rooms to read books, annotate pages, debate arguments, and shape knowledge. In a world that often feels fragmented, libraries remind us that our species is still capable of collective enlightenment.

As long as there are libraries, there is hope.

As long as there are young people hunched over books, there is a future worth fighting for.

And as long as we preserve places like this — vast, warm, light-filled, reverent — our civilisation will continue to write itself into being.

Yesterday I entered a library looking for a desk.

I left having recovered my faith in human curiosity.

And perhaps that is the true gift of a library:

it does not simply store knowledge —

it awakens the desire to create more of it.

“Education is the point at which we decide whether we love the world enough to assume responsibility for it.” – Hannah Arendt

If you love the world enough, go back to a library. Sit down. Read something difficult. Support these spaces. They are still where civilisation renews itself.