Electric cars are sold to us as the clean, ethical future: the simple solution to petrol, emissions, and climate collapse. No exhaust pipe. No fumes. No guilt. Drive electric and you’re doing your part.

But the longer I listen to the certainty around EVs — the smug finality, the “case closed” tone — the more I suspect we haven’t solved the problem at all. We’ve simply moved it.

Because “zero emissions” is only true in one narrow sense: electric cars don’t emit at the tailpipe. That matters for city air quality, and it’s not trivial. But climate impact isn’t just about what comes out of the back of the vehicle. It’s about the whole chain: extraction, manufacturing, electricity generation, and end-of-life disposal.

And yes: in many cases, electric cars really are better on the climate. A major life-cycle analysis has estimated that battery electric cars sold in Europe today can produce dramatically lower overall greenhouse-gas emissions than comparable petrol cars. That’s a real advantage, and it’s worth acknowledging.

But “better than petrol” doesn’t automatically mean “clean.” It doesn’t mean “ethical.” And it certainly doesn’t mean “no victims.”

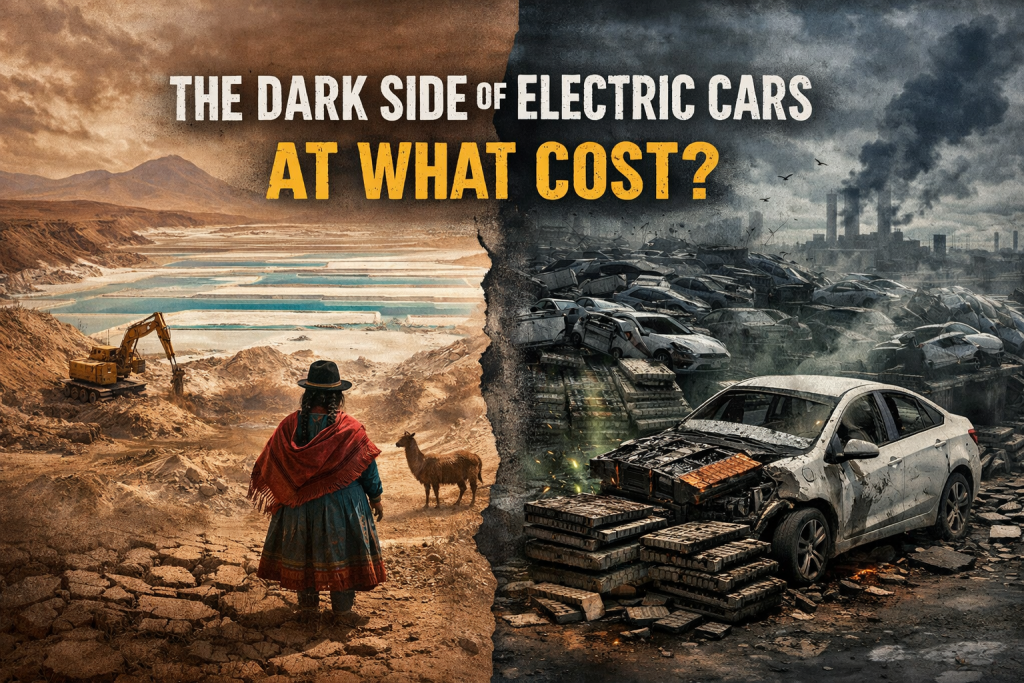

The modern electric car runs on more than electricity. It runs on minerals — and minerals have to be ripped out of the earth. The new fuel of the “green future” isn’t oil alone: it’s lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and more. And the extraction doesn’t happen in glossy European showrooms. It happens in places where ecosystems are fragile, water is scarce, and the people who live nearby often have far less power to resist the pressure.

Chile is frequently held up as a symbol of this new reality. In the Atacama region, concerns have been raised for years about lithium extraction and water stress in an already arid landscape. And while “displacement” doesn’t always mean literal bulldozers and forced removals, communities can still be displaced in practice, when resources shrink, livelihoods collapse and the land becomes harder to inhabit. You don’t always need an eviction notice to be pushed off your own future.

Then comes the question nobody wants to picture too clearly: what happens when millions of EV batteries die?

Batteries degrade. Capacity drops. Replacement costs bite. Cars are written off. And suddenly we’re not looking at a futuristic revolution, we’re looking at a looming waste problem. We are manufacturing the next century’s landfill with a smile on our faces, because it feels cleaner today.

Yes, recycling exists. Yes, there are second-life uses for some batteries. Yes, policymakers talk about circular economies. But the scale is the issue. Recycling infrastructure doesn’t magically appear just because consumers feel virtuous. It requires systems, enforcement, investment, and time — and at the moment, the global EV rollout is moving faster than the uncomfortable questions that should be travelling alongside it.

So why does this side of the story still feel strangely muted?

Partly because it’s complex, and complex stories don’t trend. But partly because the car industry is not politically neutral. The automobile sector has been one of the most powerful lobbying forces shaping transport policy, regulation, and public messaging for decades. That doesn’t require a secret conspiracy. It only requires something much more ordinary — influence, money, access, timing, and the gentle steering of what gets taken seriously.

This is the deeper danger: the electric car has become a moral symbol. Question it and you’re treated as pro-oil. Doubt it and you’re dismissed as anti-progress. But this isn’t how ethical responsibility works. A solution isn’t automatically good because it comes wrapped in green language.

Electric cars may reduce emissions. But they don’t end extraction. They don’t end harm.

We’re not transitioning from dirty to clean. We’re transitioning from visible pollution to invisible supply chains, from smoke in our cities to disruption in deserts we’ll never visit.

So yes: electrification may be part of the future. But only if we stop treating it like a miracle and start treating it like what it really is: a trade-off. A compromise. A human project, built inside a world of scarcity, power and competing interests.

If we want an energy transition worthy of the name, we need more than new engines. We need transparency, better public transport, enforceable standards, serious recycling systems and the courage to count the human cost, not as an inconvenient footnote, but as part of the moral equation.

“A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

— Aldo Leopold