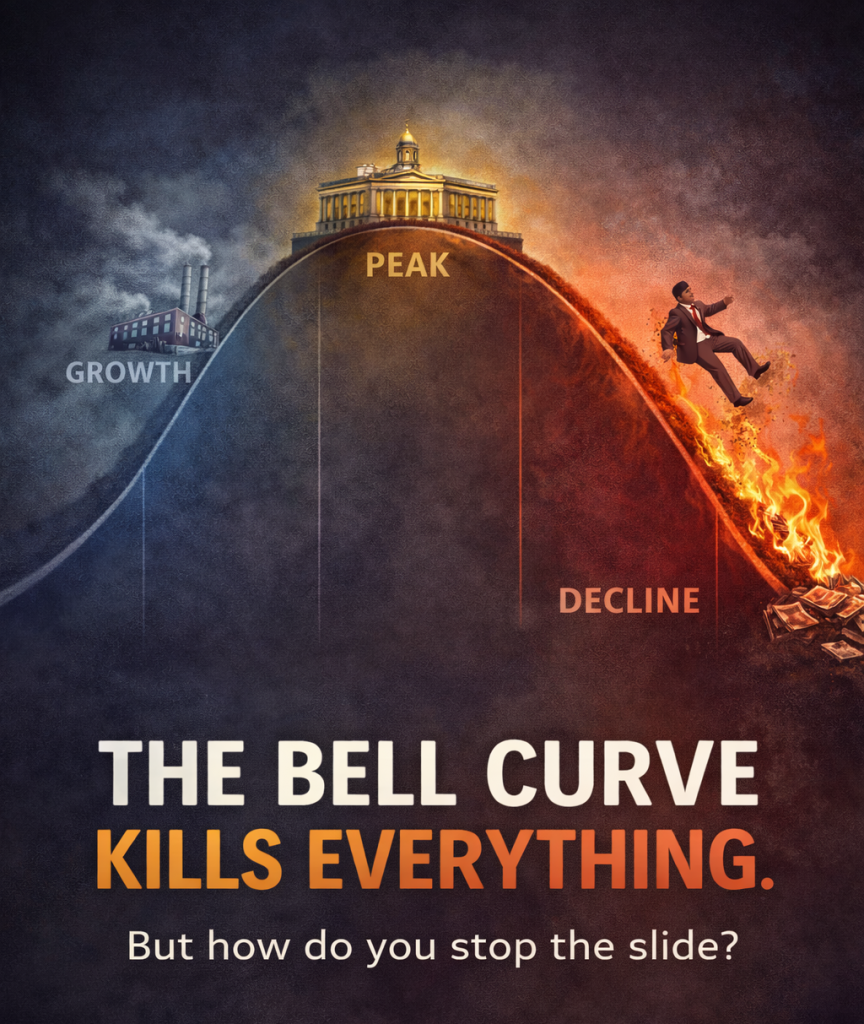

Every organisation has a bell curve.

Every organisation has a bell curve.

From the smallest start-up in Berlin… to the United States of America.

From a school, a church, a university department, a political party to an empire.

It’s always the same arc:

-

- Growth (energy, hunger, imagination)

- Peak (confidence, dominance, self-belief)

- Decline (bureaucracy, complacency, fear, decay)

This is not cynicism. It’s recognising a pattern of reality.

The question most leaders avoid

Be brutally honest: where is your organisation right now on the curve?

And when did you last hear your senior team ask that question out loud?

Because the bell curve isn’t a risk. It’s a default trajectory. It is what happens when success turns into comfort, comfort turns into protectionism, and protectionism turns into denial.

So what will you do? Ignore it and die quietly? Be honest about it and decline anyway? Or be honest about it and start building renewal structures now—before the slide becomes irreversible?

And there’s a sharper option leaders rarely admit exists: leave. Sometimes the most rational decision is to step off a sinking ship and stop lending it your competence.

History suggests the curve can’t be stopped.

And right now we’re watching it at scale—a global shift in momentum from West to East.

But I do think decline can be slowed. Here are my ideas:

1) Limit oligarchy. Increase real democracy.

When power concentrates, reality gets filtered. Bad news stops travelling upward. Loyalty becomes more valuable than truth. A leadership class forms that primarily exists to keep itself in place.

That’s not a theory. It’s the story of countless organisations—and empires.

When decision-making is captured by an inner circle, the mission becomes secondary. The organisation starts protecting status rather than producing value.

Democracy inside an organisation doesn’t mean chaos. It means distributed intelligence: people closest to customers, systems, classrooms or frontline work have meaningful influence over what must change.

2) Build for the next generation, not the next quarter.

Short-termism is a slow form of self-harm.

A company can hit its numbers while hollowing itself out: talent loss, declining product quality, decaying trust, shrinking learning capacity. The spreadsheet looks fine—until it doesn’t.

And there’s a more subtle failure inside that: leaders often build for their own peer generation, when they should be studying the people 10–20 years younger. That’s where the next expectations, habits, technologies, and cultural defaults are forming, long before they show up in your revenue chart.

What feels “risky” to today’s leadership often feels obvious to the next cohort.

And what feels “obvious” to today’s leadership can look obsolete almost overnight.

This is why so many organisations are blindsided by disruption: they optimise for the present, then act shocked when the future arrives.

If your planning horizon is shorter than your product lifecycle or your employees’ careers, you’re not sowing. You’re only maintaining and harvesting.

3) Hold ethical values steady (don’t drift in panic).

Organisations rarely collapse because of one mistake. They collapse because of moral improvisation.

In a crisis, values become “flexible.”

In growth, values become “optional.”

At the peak, values become “PR.”

Trust doesn’t usually die in a scandal. It dies in a thousand rationalisations.

Ethical steadiness isn’t virtue-signalling. It’s strategic. Trust is a form of capital, and once it’s spent, it is brutally slow to rebuild.

4) Respect history, but don’t worship it.

Tradition can be wisdom. Or it can be a velvet coffin.

The most dangerous sentence in any institution is:

“But this is how we’ve always done it.”

That phrase has probably been spoken in every declining empire, every decaying school system, every complacent corporation, and every institution that mistakes inertia for stability.

Keep the lessons of history—but don’t let history become your excuse for refusing change.

5) Reward truth-tellers, not loyalists.

Cultures fail when honesty becomes career suicide.

When an organisation punishes uncomfortable truth, it trains people to produce comforting noise. Metrics get gamed. Problems get rebranded. Rot gets managed instead of removed.

If your culture doesn’t actively protect dissenters, you don’t have “alignment.” You have fear.

One of the clearest predictors of decline is a leadership team that only hears what it wants to hear and then mistakes that for reality.

6) Break the organisation on purpose (real renewal, not cosmetic change).

Here’s the missing lever most leaders refuse to pull:

Healthy organisations schedule their own disruption.

Unhealthy ones wait until disruption happens to them.

This is deeper than “innovation.” It’s constitutional design:

-

- sunset clauses on programmes and teams

- rotation of leadership roles

- independent internal “red teams” tasked with challenging assumptions

- simplification by cutting products, meetings, layers and rules

- and, when needed, radical reinvention of mission, structures, and incentives—not just a new logo

There’s a famous story about Steve Jobs in a meeting, sweeping clutter off a table and saying, in effect: start again—what actually matters? Whether or not the anecdote is perfectly literal, the point is real:

Most organisations don’t fail because they lack intelligence.

They fail because they can’t bear to delete what once made them successful.

“How did you go bankrupt?”

“Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

— Ernest Hemingway