On 11 January 2026, Sky News ran a piece with a headline that would have sounded unlikely a decade ago: “How did Gen Z become the most religious generation alive?”

The article reports an uptick in religious belief and church attendance among young adults, with social media playing a surprising role in how faith is “discovered” and spread: short-form religious content on TikTok and Instagram, influencers speaking openly about God, and churches receiving enquiries from young people who first encountered religion online.

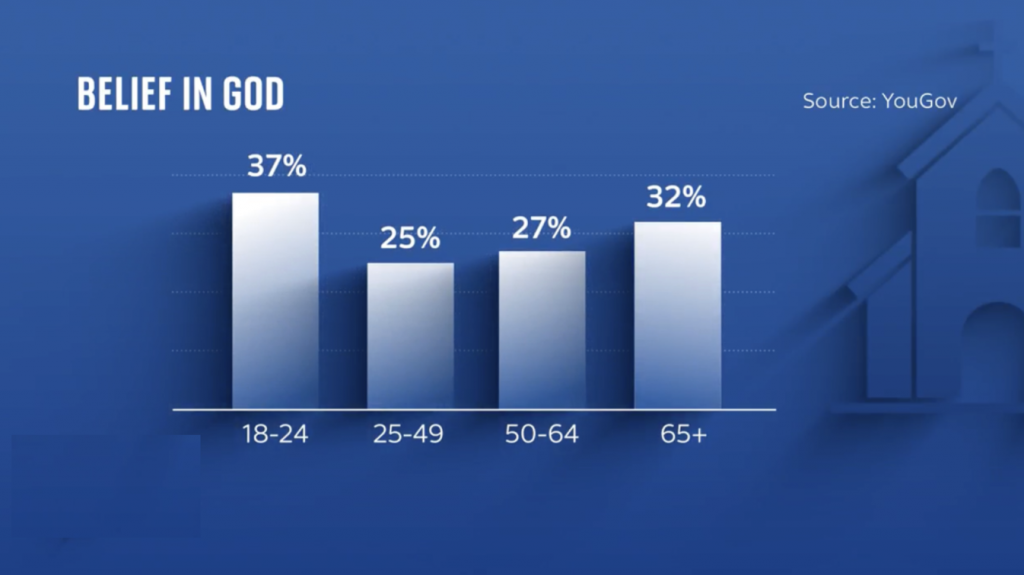

Sky’s piece includes voices from Christian influencers who say they’re seeing a noticeable rise in young people asking how to get involved, and it references YouGov data suggesting a marked shift: among 18–25s, monthly church attendance rising from 7% (2018) to 23% (2024), and belief in a higher power rising from 28% to 49% across the same period.

Even the sceptics appear in the report—young atheists who say this doesn’t match what they see online, or who wonder whether the change is temporary and pandemic-shaped.

So: something is happening. And if we care about society, about meaning, about the moral atmosphere we all breathe, we should pay attention.

Why this makes sense (even if you’re not religious)

I teach university students. I write about social meaning. And I have to admit: the trend itself is not mysterious to me.

When a society loses confidence in its shared story, people don’t become “purely rational.” They become hungry.

For a long time, the West lived off inherited moral capital: ideas of human dignity, restraint, compassion, truth-telling, fidelity, responsibility—values that were once anchored in a Christian metaphysics, then carried forward as if they could survive on sentiment alone.

But sentiment doesn’t sustain a civilisation.

What we increasingly offer young people instead is:

-

- Ethical drift: everything negotiable, nothing binding

- Performative role models: influence without character, aesthetics without responsibility

- Thin narratives: “be yourself,” “live your truth,” “manifest your future” — slogans that collapse under suffering

- A destabilised world: economic fragility, housing impossibility, ecological anxiety, war returning as background noise

Under those conditions, it is almost inevitable that many will reach for something older and firmer than the modern self. Something that says:

-

- this is real

- this is right

- this is wrong

- your life is not an accident

- your suffering is not meaningless

- there is a way through

And in the Western world, that “something” is most readily available in Christianity.

Which churches will benefit most

If Gen Z is turning toward Christianity for meaning and stability, we should be honest about where the gravitational pull will land.

It will not primarily be the churches that sound like ritual, bored faces and committees.

It will be the churches that sound like conviction.

The kinds of churches most likely to grow are the ones that offer:

-

- non-negotiable truth (not “your personal journey,” but The Answer)

- a strong identity (“this is who we are; this is how we live”)

- high emotional impact (music, lighting, atmosphere, collective intensity)

- clarity about enemies (the world, the devil, “compromise,” secular decadence)

- belonging that feels immediate and total

The Sky News article points to the rise of Christian content on TikTok and influencer culture around faith.

That ecosystem naturally rewards certainty, compression, drama, and transformation narratives—all things charismatic and fundamentalist Christianity has always been good at packaging.

If you want a religion that fits social media, you will end up with the kind of religion that performs well on social media.

And that is where my caution begins.

My stake in this: I used to be one of them

I am not writing this as an anti-Christian hit piece.

I am writing this as someone who once stood inside that world—as a pastor, not merely a visitor. I believed. I preached. I led people. I sold my house and car and moved abroad with my family. I was part of the machinery that makes a high-commitment church feel like home and destiny at the same time.

I no longer believe in God.

And because I know what these churches can do—both the beauty and the damage—I want to say something directly to any Gen Z reader who is moving toward Christianity because the world feels hollow and unstable.

You are not foolish for wanting meaning.

You are not stupid for wanting a moral anchor.

But you may be walking, without realising it, into a system designed to take more from you than it gives.

So let me offer a warning, not against faith as such, but against a particular style of faith that is increasingly likely to catch you.

Four warnings before you hand over your life

1) It offers “ultimate truth” — but it cannot prove it

Fundamentalist Christianity sells certainty.

It tells you the world has a secret structure and it possesses the key: virgin births, miracles, demons, healings, resurrections, prayers that alter reality. It gives you a total explanation and calls that “faith.”

But human beings will believe almost anything if it fits the narrative they are offered—especially when the narrative arrives wrapped in community, music, belonging, and moral purpose.

That is not an insult to believers. It is an observation about humans.

A strong story can feel true even when it isn’t.

And the stronger the story, the more it demands you interpret everything through it: your sexuality, your friendships, your doubts, your pain, your ambitions, your money, your family.

Once you interpret reality through a sacred script, the script becomes self-sealing. Evidence against it becomes “temptation” or “attack” or “pride.”

That isn’t truth. That is a closed system.

2) It trains you to call the selflessness “love” — but salvation is still about you

There is a reason Nietzsche was so ferocious about Christianity.

Christianity can produce remarkable acts of compassion—real kindness, real service. Many Christians are genuinely good people.

But at the structural level the religion often contains a hidden centre of gravity: your soul, your salvation, your standing before God, your purity, your afterlife.

Even love can become instrumental:

-

- I love you because I must be Christlike

- I witness to you because your conversion validates my worldview

- I “forgive” you because it keeps me clean

- I help you because it stores treasure somewhere else

When salvation is the central preoccupation, the self never truly exits the stage.

You may feel you are becoming “more loving,” but you may also be becoming more morally anxious, more self-monitoring, more dependent on approval, more afraid of your own doubt.

3) The sacrifices will not deliver what is promised

High-commitment Christianity often sells a paradox:

Give up the world and you will gain joy.

And sometimes, at first, it works. Early conversion can feel like oxygen: clarity, unconditional love, a new tribe, a new identity, a new sense of direction. In a lonely world, that is powerful.

But over time the bargain changes.

You will be asked to sacrifice things that are not merely “sinful,” but simply human:

-

- parts of your identity that don’t fit the template

- questions you’re not allowed to keep asking

- desires you must rename as temptation

- relationships that become “unequally yoked”

- your own inner authority

And here’s the trap: the moral standard is often impossible.

You will be told to be holy, pure, humble, grateful, surrendered, joyful, obedient, servant-hearted, faithful, prayerful, disciplined, generous, forgiving, and to treat doubt as rebellion.

That produces one of two outcomes:

-

- you become a performer: outward righteousness, inward fracture

- you become perpetually guilty: never enough, never clean, never sure

Neither is freedom.

4) You may be entering a soft prison you won’t easily leave

This is the warning I most want to underline.

A church can become a total social world:

-

- your friends

- your dating pool

- your weekends

- your music

- your language

- your moral framework

- your sense of being “safe”

And once that happens, leaving is not like changing a hobby. It is like exiting a country.

The gravitational pull is real:

-

- leaders frame departure as betrayal

- friends become wary, then distant

- doubts must be hidden or confessed

- your identity becomes fused with the group

- your fear of “backsliding” keeps you inside

Even if nothing “cultic” is happening, the system can still function like a sect: high belonging, high cost, high control.

And if your life later falls apart, as lives sometimes do, the love you thought was unconditional can become conditional very quickly.

I have lived that.

When my own life imploded, many of the people who had once spoken the language of grace stepped back. Disappeared. Some rewrote history. Some behaved as if I had never existed. It was as though my entire Christian life was deleted overnight.

And the cruelty of that is specific: because Christianity is often sold as the cure for rejection. You think you are finally safe.

Then you discover you were safe only while you were useful, coherent, and compliant.

A closing word to Gen Z: don’t outsource your hunger

If you are drawn toward Christianity because the world feels unstable, I understand.

The moral void is real.

The longing for meaning is not childish. It is the most adult thing about you.

But please, before you hand over your identity, time, sexuality, money, and inner authority to a high-commitment religious system—pause.

Ask:

-

- Does this community make me more honest, or merely more certain?

- Does it strengthen my conscience, or replace it?

- Does it widen my compassion, or narrow my world?

- Can I doubt here without being punished?

- If I leave, will love remain?

- What is the cost of belonging—and who benefits?

If you still choose faith, choose it with open eyes.

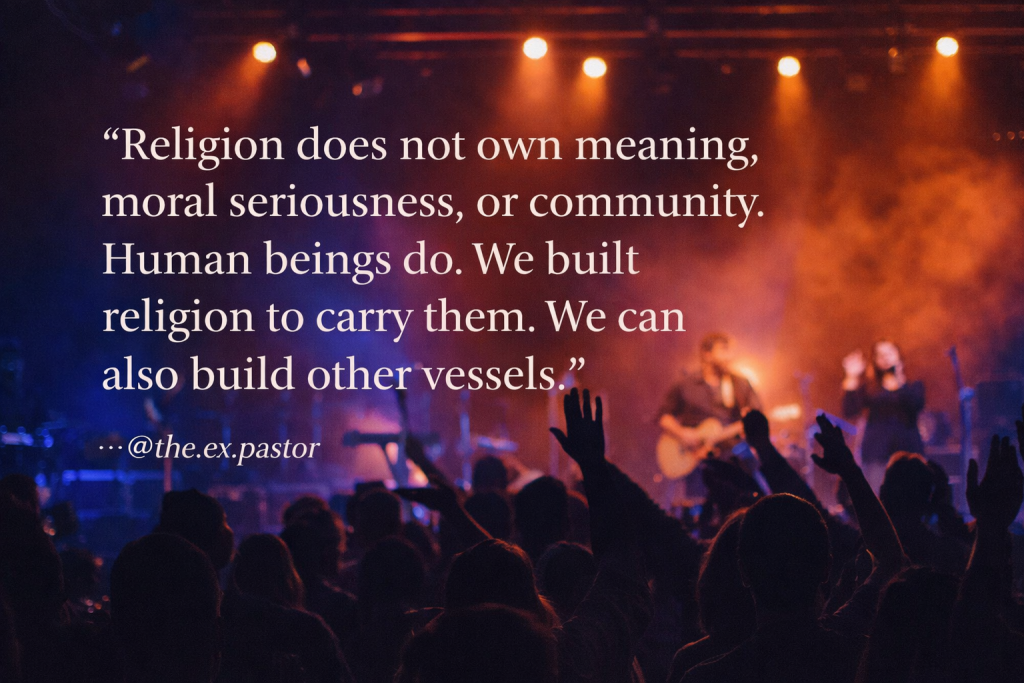

And if what you are really seeking is meaning, moral seriousness, and community, remember: religion does not own those things. Human beings do.

We built religion to carry them. We can also build other vessels.

The point is not to mock your hunger.

The point is to protect you from people who know exactly how to use it.

“I might believe in the Redeemer if his disciples looked more redeemed.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche