Over the past decade, British governments have repeatedly demonstrated that fiscal limits are flexible. When spending is framed as urgent, unavoidable, or tied to national security, the state borrows freely and at scale. When spending concerns education, healthcare, or the living standards of poorer pensioners, we are told, with equal confidence, that there is no money.

The contradiction is not hidden. It is simply normalised.

The fiction of scarcity

The UK does not suffer from an absolute inability to spend. It suffers from a selective definition of what counts as affordable. Public borrowing is not rejected in principle; it is filtered by legitimacy.

Debt incurred for defence, border enforcement, or security infrastructure is framed as realism, regrettable but necessary in a dangerous world. Debt incurred to maintain schools, fund care, or prevent old-age poverty is framed as indulgence, risk, or irresponsibility.

This distinction is not economic. It is rhetorical and moral. Once embedded, it removes priorities from democratic debate and replaces them with a language of inevitability.

Where the money goes

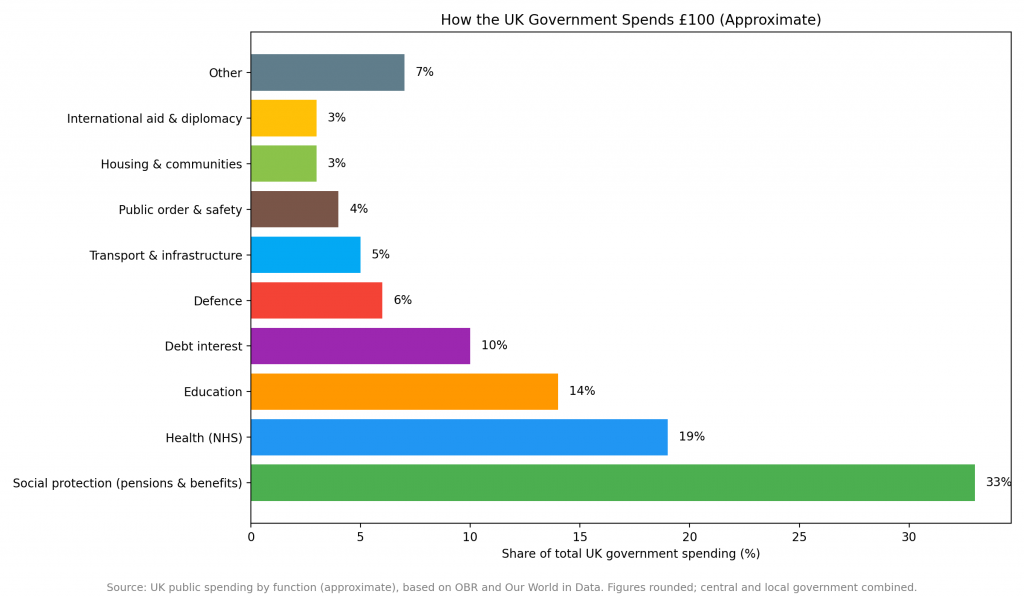

The overall structure of UK government spending already tells part of the story.

How the UK government spends £100 (approximate).

Based on OBR, HM Treasury, and Our World in Data. Figures rounded; central and local government combined.

At first glance, the picture appears balanced. Social protection, healthcare, and education account for a substantial share of spending. Defence, by contrast, is not the largest item.

But this is precisely where the debate often goes wrong. The issue is not whether defence dominates the budget. It is which areas of spending are treated as politically untouchable.

One category in the chart deserves particular attention: debt interest. A significant share of public money now goes simply to servicing past decisions, producing no public services at all. Yet even this is treated as unavoidable, while investments in human and social infrastructure are endlessly questioned.

What is protected over time

To understand political priorities, we need to look not just at levels of spending, but at what is protected from decline.

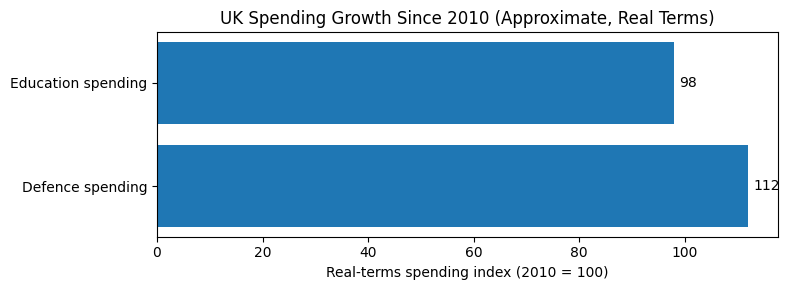

UK spending growth since 2010 (real terms, index: 2010 = 100).

Approximate indices based on Treasury, IFS, and OBR data; figures rounded for clarity.

Since 2010, UK defence spending has grown modestly in real terms. Education spending has failed even to keep pace with inflation.

This divergence matters. Growth here does not imply excess, nor does stagnation imply neglect by accident. It reflects which areas of public life are shielded from erosion, and which are allowed to decline quietly, year after year.

Defence is treated as structurally non-negotiable. Education is treated as adjustable.

Managed distraction and political theatre

This hierarchy of priorities is sustained by a wider political and media environment that rarely lingers on structural questions.

Public attention is instead drawn toward asylum boats, royal scandals, party infighting, leadership personalities, tactical U-turns, and culture-war skirmishes. Each may be newsworthy in isolation, but together they form a fog, absorbing outrage while larger financial commitments pass with limited scrutiny.

While headlines fixate on spectacle, long-term spending decisions are presented as technical necessities rather than political choices. Defence increases are framed as serious and sober. Social spending is framed as contentious, expensive, or unrealistic.

What “we can’t afford it” really means

The phrase “we can’t afford it” has become a shorthand for this does not rank high enough. It signals which forms of harm the state is willing to tolerate, and which it is determined to prevent.

In contemporary Britain, the harms associated with underfunded care, deteriorating schools, and pensioner poverty are treated as regrettable but acceptable. The risks associated with under-spending on defence or control are treated as intolerable.

The issue that remains

The real test of a society is not what it claims it cannot afford, but what it never seriously debates cutting.

Until this issue is faced honestly, debates about affordability will continue to obscure what is really at stake. The elephant will remain in the room: visible, substantial, and politely ignored.

“Budgets are moral documents.”

— Jim Wallis