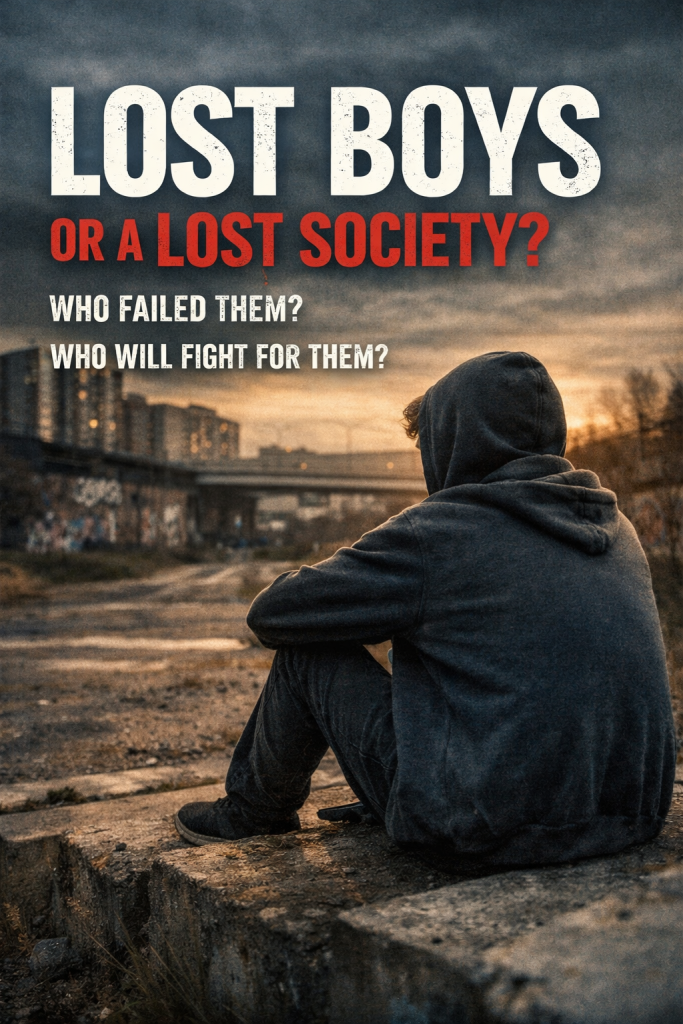

In response to Sky News, “The Lost Boys: How do you help fatherless teens who ask: ‘Am I the problem?’” (17 February 2026)

What if the crisis facing Britain’s boys is not primarily about absent fathers, but about a society that no longer knows how to raise them?

The recent Sky News report on fatherless teenage boys is careful, empathetic and clearly motivated by concern. It follows several boys growing up without consistent paternal presence, explores mentoring initiatives such as the GOAT Boys project and situates individual stories within a stark statistical landscape. Boys are lagging behind girls at school, men are dominating youth prison populations and young males increasingly disengaged from education and work.

The article deserves to be taken seriously. But it also reflects a broader tendency in public debate: to locate the problem too narrowly in fathers themselves — their absence, their failures, their irresponsibility — while overlooking the deeper institutional, cultural and economic structures that shape boys’ lives, whether their fathers are present or not.

If we want to help boys, we must go deeper.

I write as a teacher and teacher trainer with four decades of experience across Britain, Europe, and Mumbai, and also as a working-class boy from the north of England who, against the odds, obtained a scholarship to read modern languages at the University of Oxford. That trajectory gives me neither moral superiority nor nostalgic certainty. It does, however, give me a long view of how institutions speak and whom they fail to hear.

Boys’ underperformance: a statistic that explains too little

It is statistically true that boys underperform girls across most educational metrics, from early schooling through to A levels. But this fact, endlessly repeated, is not in itself explanatory.

The assumption often smuggled into public discussion is that boys would perform better if only their fathers stayed at home or returned. This is a comforting idea: simple, moral and politically safe. It is also inadequate.

The deeper issue is that our education system remains fundamentally antiquated: its syllabuses, pedagogies and assessment regimes are designed for compliance, abstraction, and credential-accumulation rather than meaning, relevance or lived intelligence. They were built for a pre-digital, class-stratified society and have never been fully rethought for a media-saturated, post-industrial world.

When I conducted research at the University of Sussex some years ago, I interviewed boys after a mock GCSE maths examination in which many had underperformed. Several explained something striking. They knew the mathematically correct answer — for example, the precise change returned by a Coca-Cola vending machine — but assumed it must be wrong. In real life, they said, Coca-Cola costs more than that so the amount of change given had to be less. So they altered their answers to make them “realistic”.

They were penalised for intelligence that refused to suspend reality.

This was not a failure of reasoning. It was a collision between lived rationality and institutional rationality. The institution won and the boys lost.

Educational language in Britain remains overwhelmingly middle-class in its assumptions, abstractions and modes of expression. Working-class boys often understand the task but not the game. They disengage not because they are incapable, but because the system repeatedly signals that what they really know does not count.

“If we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday’s, we rob them of tomorrow.”

— John Dewey

Schooling, masculinity and the absence of ordinary men

Around 85–86% of primary school teachers in the UK are women. This is not a criticism of women teachers, many of whom do extraordinary work. It is an observation about institutional reality.

Primary schools are now among the few remaining public spaces in which many boys encounter almost no ordinary adult men at all. This matters for boys who already lack stable male presence at home or whose primary exposure to masculinity comes via social media.

Role models are not ideological constructs. They are relational. Boys need to see men reading, explaining, disciplining, failing, apologising, and persisting. Not as “mentors” or “interventions”, but as part of everyday life.

When this is absent, schools inherit a burden they were never designed to carry.

Father absence = delay discounting

Where father absence does matter educationally is not primarily in emotional damage, but in how boys learn to relate present action to future consequence.

Psychologists describe this as delay discounting: the tendency to devalue future rewards in favour of immediate ones. The consistent presence of a father often helps a boy internalise a basic cognitive link: what I do now shapes what becomes possible later.

When that link is weak or absent, education becomes almost unintelligible. Our system demands that students tolerate years of deferred gratification — irrelevant knowledge, abstract assessments, meaningless hurdles — in order to unlock a distant, hypothetical future. Boys who lack a lived sense of future consequence struggle to sacrifice present enjoyment for credentials that feel unreal.

As one headteacher in the Sky News article puts it:

“It’s really tricky sometimes to try to get into a young boy’s head the importance of passing their GCSEs, if someone outside school is offering them £500 to do a bit of work at the weekend for an illegal endeavour.”

Girls, for a range of social and psychological reasons, tend on average to navigate this demand more successfully. That does not mean the system is working. It means it is selectively survivable.

Prison, punishment and the confusion of severity with safety

Boys make up around 98% of the youth prison population. This is not a moral failure of boys. It is an institutional failure of the state.

Britain’s criminal justice system remains far quicker to incarcerate than to rehabilitate. Political and media incentives favour visible punishment over slow repair, toughness over effectiveness. Yet the evidence is overwhelming: harsher sentencing does not reduce crime in the long term.

Incarceration, especially of young men, often functions less as prevention than as delayed social accounting, the point at which the cost of earlier educational, familial and social failure finally appears on the balance sheet.

Justice matters. Victims matter. But revenge is not rehabilitation, and severity is not safety.

Why professionals cannot replace fathers

The mentoring initiatives described in the Sky News article are sincere and often impressive. They should not be dismissed. But we should also be honest about their limits.

Professionalised care cannot substitute for the long, morally binding authority of a biological or adoptive father who is present over time. Many mentors speak a language that remains distant from the lived reality of working-class boys. Acronyms, programmes, and “projects” may invite engagement, but they cannot create belonging.

This is not ingratitude. It is realism. Systems can support families; they cannot replace them.

What the boys themselves are actually saying

The most revealing moments in the Sky News article are not about fatherhood at all. They are about socially constructed meaning.

The boys speak of learning to tie a tie from YouTube. Of asking themselves, “Am I enough? Am I the problem?” They speak of emotional restraint, of being expected not to feel, not to speak, not to falter.

Gareth Southgate captures this precisely:

“Young men are suffering. They are grappling with their masculinity and their broader place in society.”

This is not a parenting issue alone. It is a crisis of social imagination.

The hidden cost: to the state, the economy and social trust

The cost of this failure is enormous and is rarely calculated honestly.

-

- Incarceration: Keeping one person in a closed prison in England and Wales costs roughly £54,000 per year. Multiply that across a heavily male prison population, and the fiscal consequences are staggering.

- Healthcare: Smoking alone costs English society tens of billions of pounds annually, including around £1.8–1.9 billion in direct NHS costs. Men remain disproportionately affected by smoking-related heart disease and cancers.

- Addiction: Over 300,000 adults are currently in contact with drug and alcohol treatment services, the majority of them men. Prevention is cheaper than cure; relapse is more expensive than early intervention.

- Housing and family breakdown: Around 100,000 divorces occur annually in England and Wales. Family separation often creates two households where one existed before, intensifying housing pressure — a factor almost never mentioned in political discussions of the housing crisis.

- Intergenerational effects: Children of divorced parents are statistically more likely to experience relationship instability themselves, compounding social and economic costs over time.

We argue endlessly about government borrowing, borders and defence spending, but rarely about the quiet, cumulative cost of boys who never quite find a place in society.

Adolescence and the limits of parental culpability

The Netflix series Adolescence makes an important and often overlooked point. Its central character has a good father and a good mother — and things still go wrong.

Social media, peer dynamics, algorithmic masculinities and online grievance cultures now shape boys’ inner worlds in ways parents cannot fully control. Parents remain responsible. Absent fathers must own their absence. But culpability cannot be total.

Responsibility is lifelong. Control is not.

Conclusion: prevention, not panic

If prevention matters more than cure, then three things follow:

First, we must radically rethink education: its language, its assessments, and its relationship to real life.

Second, we must invest moral seriousness in something other than punishment, debt-reduction and symbolic toughness.

Third, we must collectively decide that boys are not problems to be managed, but human beings to be formed.

It takes more than a village to raise a healthy boy.

It takes a society willing to mean what it says about the future.

A society is not judged by how it punishes those who fail within it,

but by how seriously it takes the work of forming those who will one day inherit it.