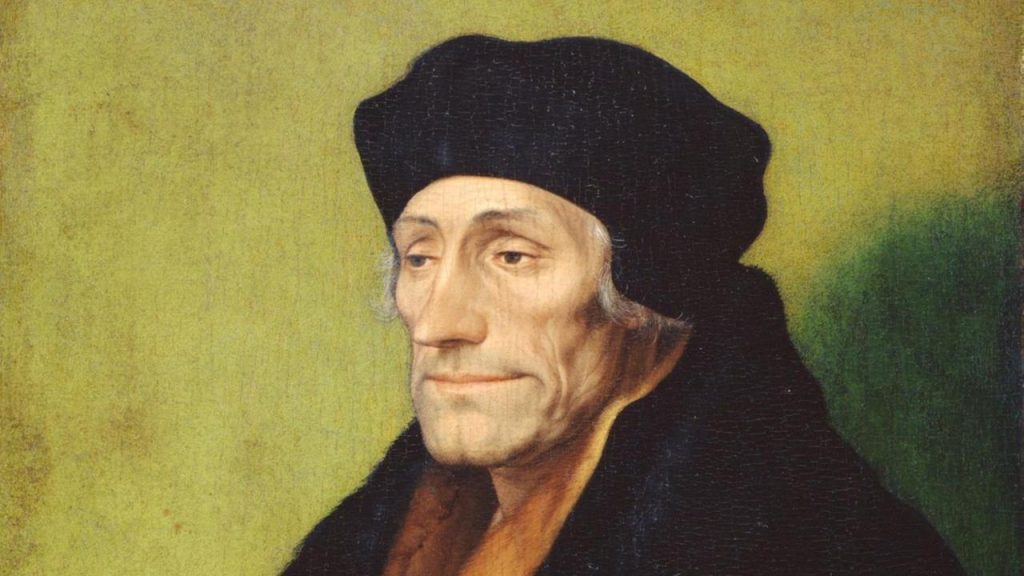

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam

Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466–1536) is often regarded as the pioneer of historical-biblical criticism — a discipline that continues to polarise attitudes to the Bible today.

A highly gifted academic, a Catholic priest, and in many ways one of the first genuine citizens of Europe, Erasmus was also the illegitimate son of a priest. Both his parents died of the plague when he was a teenager. These hardships helped shape his lifelong belief in synergism (salvation is a work of both God and human co-operation), in contrast to the monergism (salvation is a work of God alone) preached by Luther and many Protestants since the Reformation.

Erasmus the Humanist

Erasmus was a pacifist who wanted Christianity to be lived out in daily practice. He feared that Luther’s belligerence would fracture the church — which is exactly what happened. Yet Erasmus was also a product of his time: a humanist who sought to move faith away from lofty scholastic debates and root it once again in the lives of ordinary people.

That concern drove him to produce accurate translations of the Bible from authentic manuscripts, placing them into the hands of ordinary believers.

The Problem of the Vulgate

For centuries the church relied on the Vulgate, a 4th-century Latin translation. When Erasmus compared it with manuscripts in Greek and Hebrew, he found countless errors — mistranslations, omissions, outright mistakes.

This raises uncomfortable questions for fundamentalists:

-

If the Bible is the infallible Word of God, why did God permit flawed versions for the first 1,500 years of church history?

-

If Christians are meant to base their lives on Scripture, what did they do during the early centuries when no agreed New Testament even existed — and when its canon was decided by human choices?

-

What if more accurate manuscripts were discovered tomorrow? Would faith collapse?

-

Why did God wait until the 18th century for scholars to unearth more reliable manuscripts, leaving believers with errant texts for nearly 1,700 years?

Pragmatists vs. Fundamentalists

These questions split Christians into two camps. Erasmus and his heirs take the pragmatic view: human errors in transmission do not negate the central message of Jesus.

Fundamentalists, by contrast, insist that every word of Scripture is directly inspired, perfectly preserved, and must be correctly interpreted in “synergy with the Spirit.” They claim a monopoly on truth while conveniently overlooking the centuries of textual mistakes God apparently permitted.

Seeds of Criticism

Erasmus thus planted the seeds of modern historical-biblical criticism. If the text contains human flaws, then textual criticism is necessary. From there follow source, form, and literary criticism.

To many fundamentalists, these methods are “tools of the devil.” But the devil himself is a mythical construct — a figure invented by those in power to keep ordinary people in fear and obedience. What fundamentalists really fear is the erosion of their authority over naïve believers.

Erasmus Ahead of His Time

Erasmus held on to his synergistic convictions, alienating many theologians of his day. In hindsight, he was far ahead of his time.

And the core question remains: Which kind of Christian most resembles Jesus?

-

The one who lives daily in gratitude, prayer, and service, applying the main tenets of Scripture with humility?

-

Or the one who thunders fundamentalist slogans while ignoring beggars, railing against minorities, and collaborating in the destruction of the planet?

Which vision reflects the heart of Jesus more closely: Erasmus’ synergism, where humans freely cooperate with God to make the world better, or Luther’s monergism, where salvation is a matter of predestined grace and the rest are damned from birth?

After all, in Matthew 19, Jesus gave the rich young man a choice.

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

— F. Scott Fitzgerald